Dr Can Erimtan

21st Century Wire

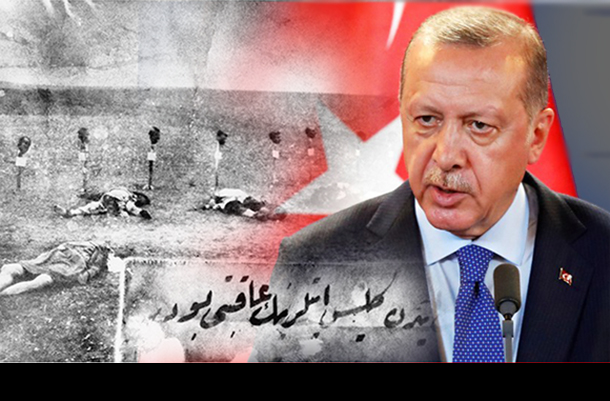

The present Republic of Turkey was built by the followers of Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), known as Kemalists, who for the most part had been members of the Committee for Union and Progress (hence Unionists), the political movement that led the Ottoman state to its demise in the Great War. In this 21st century then, an Islamist political movement, with its roots in the Naqshibandiyyah brotherhood, has brought about the end of Atatürk’s example and an officially-approved Ottoman revival (as a shorthand for an Islamic réveil). In spite of their differences, these two permutations of the Turkish state – Kemalist and Islamist – possess an eerily similar relationship with a specific aspect of the Turkish past, a particular episode that took place in the early years of the previous century: the Armenian Genocide.

Armenians and Americans

U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham from South Carolina is one of the most mercurial of political operators in American politics. Starting out as a vocal supporter of Turkey, then recently becoming one of the the main Kurdophilia proponents in the U.S. Congress, he’s now once again become Turkey’s saviour, blocking a “Senate resolution recognising the Armenian genocide.” This issue of the ‘Armenian genocide,’ which now seems to have come to greater public and popular attention as a result of Kim Kardashian’s ‘passionate’ and ‘eloquent’ advocacy, constitutes a major controversy in the Republic of Turkey as the successor state to the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia (and western Thrace). In fact, some would argue that the ‘New Turkey‘ constructed and ruled by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (or the Prez) and his Justice and Development Party (or AKP) has now placed itself in the direct line of succession with its Islamic forebears in the area – not just the Ottomans (1299-1922), but also the Seljuks (1075-1308). And every year, this legacy comes under a great deal of global scrutiny on the 24th of April. Known as ‘Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day,’ it is the day that Ankara watches Washington closely. This year, President Trump did not disappoint, as his public statement included the Armenian expression “Meds Yeghern“ (literally ‘Great Crime’), and deftly managed to avoid the dreaded G-word. The Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin (1900-59) coined the term ‘genocide’ in 1944, which was subsequently adopted by the United Nations on 9 December 1948, coming into force on 12 January 1951, “in accordance with article XIII.” And Turkey is all but paranoid about being tarred with the term.

President Donald Trump revels with new loyal cohort Senator Lindsey Graham.

Quite recently, the U.S. House of Representatives did the unthinkable and went ahead and recognised the Armenian Genocide: the “US House of Representatives has voted overwhelmingly in favour of recognising the mass killing of Armenians by Ottoman Turks during World War One as a genocide,” reported the BBC on 30 October. In years past, American lawmakers have always managed to pragmatically dodge this Armenian bullet, but now the much-publicised but as yet unrealised genocidal extermination of the “Kurds” of northern Syria (popularly known as Rojava) in the framewok of #OperationPeaceSpring has made these lawmakers brave, braver than usual and quite willing to antagonise the Turks, even if only to spite President Trump. And many will say, at long last. Adding insult to injury, the U.S. Congress took the momentous vote on 29 October, Republic Day of Turkey (Cumhuriyet Bayramı, in Turkish) commemorating the foundation of the Turkish state in 1923. On that same day this year, House Resolution 296 was introduced by Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA) and reads as follows in summary: “This resolution states that it is U.S. policy to (1) commemorate the Armenian Genocide, the killing of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman Empire from 1915 to 1923; (2) reject efforts to associate the U.S. government with efforts to deny the existence of the Armenian Genocide or any genocide; and (3) encourage education and public understanding about the Armenian Genocide.” And the full text of the bill goes a lot further, stipulating that “the United States has a proud history of recognizing and condemning the Armenian Genocide, the killing of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman Empire from 1915 to 1923, and providing relief to the survivors of the campaign of genocide against Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Syriacs, Arameans, Maronites, and other Christians.”

Furthermore, the bill even adds that “Raphael Lemkin [himself] . . . invoked the Armenian case as a definitive example of genocide in the 20th century.” In this way, the U.S. Congress has seemingly managed to link the now much-maligned Tayyip Erdoğan with the despicable figure of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) – the South-Sudanese UN official Francis Deng has after all called “Nazi Germany’s attempt to exterminate the Jews in the country and elsewhere in Europe . . . the most extreme case of genocide.” But about a fortnight later, the Senator from South Carolina saved the day, and now Turks can sleep easy again, knowing that, come 24 April 2020, the Americans will not have the temerity of connecting the new post-Kemalist Republic with the dreaded G-word. By sheer coincidence, the Prez was recently visiting his U.S. counterpart, Donald Trump, and then he also met with several Republican senators at the White House, including the Carolinian (13 November 2019). In the White House, Erdoğan even whipped out his smartphone and proceeded to show the gathered men a specially prepared clip showing perfidious acts carried out by the PKK/YPG (Kurdish Workers’ Party/People’s Protection Units) and particularly pointing out that the SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces) General Commander Mazloum Abdi Kobani, whom Trump has actually been tweeting with, is none other than the PKK operative Ferhat Abdi Şahin. Graham then apparently grew a bit of a spine, reportedly asking the Turkish President, “[d]o you want me to get the Kurds to play a video about what your forces have done?” Still, soon after meeting with his boss and the Prez, the South Carolinian Senator blocked a similar resolution in the Senate to HR 296, afterwards telling the world that his object was not “to sugarcoat history or try to rewrite it, but to deal with the present.”

The Politics of Denial and Reconciliation

Still, about a fortnight previously, the Prez did not waste any time coming up with a suitable response, speaking to the nation on television he talked about the congressional vote as “worthless and [added that] we do not recognise it.” The AKP FM Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, for his part, called the vote “null and void,” and even made the link with Operation Peace Spring, tweeting that “[t]hose whose projects were frustrated turn to antiquated resolutions. Circles believing that they will take revenge this way are mistaken. This shameful decision of those exploiting history in politics is null and void for our government and people” (10:24 pm, 29 Oct 2019). On the other side of Turkey’s political spectrum, the opposition MP Garo Paylan, a Turkish citizen of Armenian extraction, tweeted that the “US Congress has recognized the Armenian Genocide. Because my own country [i.e. Turkey] has been denying this for 105 years, our tragedy is discussed in other world parliaments. The real healing for Armenians will come when we can talk about the Armenian Genocide in Turkey’s own parliament” (3:31 pm, 30 Oct 2019).

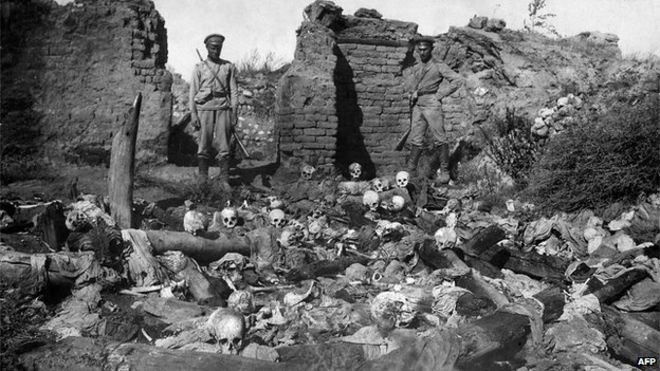

Horrific scenes in the ruined Armenian village of Sheyxalan in 1915 (Image Source: Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute/AFP)

The Armenian MP Paylan is a vocal and visible member of the HDP or the Peoples’ Democratic Party, which the West likes to call a ‘pro-Kurdish’ party, but should nevertheless really be seen as a political vehicle employed by the nation’s Kurds and its supporters, largely beholden to the imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan (popularly known as Apo). The opposition party purports to represent all the different ethnic and religious groups and sub-groups living in Anatolia, hence the inclusion of the Armenian Paylan as its MP. With regard to the issue of the Armenian Genocide, the HDP has conveniently already come clean: on 2 October 2015 the party released its elections platform which included a section that stipulated that “the [Turkish] state should issue state-level apologies for genocides and massacres committed against different groups over the years.”

Setting the Scene: A Feat of Ethno-Religious Demographic Engineering

The mere existence of this political grouping is testament to the fact that the nation state that is Turkey is far from being solely inhabited by ethnic Turks. This fact, which might puzzle most people, is rooted in late-Ottoman Unionist precedent and early-Republican Kemalist history: “Anatolia has always been home to a wide variety of ethnic and religious groups and sub-groups, and today, the makeup [of] Turkey’s population is the result of Ottoman government policies carried out in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These policies were aimed at transforming Anatolia (the heartland of the Ottoman Empire) into a Muslim homeland where refugees from the Russian Empire and the Balkans were settled. In the early 20th century, Anatolia was thus home to ethnically heterogeneous Muslim groups: in addition to a large majority of Turkish Muslims, there were Kurds, Arabs, Lazes, Muslim Georgians, Greek-speaking Muslims, Albanians, Macedonian Muslims, Pomaks, Serbian Muslims, Bosnian Muslims, Tatars, Circassians, Abkhazians and Dagestanis among others. Prior to the formulation of Turkish nationalism as an ideological binding-force, the diverse ethnic groups in Anatolia were united by their common identity as Muslims and their allegiance to the Ottoman Caliphate, abolished in 1924,” as I have explained elsewhere. These population policies came to an official culmination in the 1923 with the League of Nations-sanctioned population exchange between Greece and Turkey, when Greek- as well as Turkish-speaking Orthodox believers in Anatolia were replaced by Turkish-speaking Muslims hailing from areas previously held by the Kingdom of Greece (1832-1924).

A state-sponsored “policy of Turkification carried out in the first decades of the republican existence has meant that these various [Muslim] ethnic subgroups have in time merged with the Turkish mainstream,” after having largely replaced various native Christian population groups previously inhabiting Anatolia’s fertile plains and lands, a historical process I explained in a now more than ten-year old in-depth academic piece. And the issue of the Armenian Genocide has to be seen within the context of this grand scheme of ethno-religious demographic engineering on the part of the late-Ottoman Unionist government partly continued by the pre-Republican state in the early 1920s – after all, “the Kemalists continued with the ethnic [and religious] purification policies of the Unionists,” as expressed by the historian Dr Doğan Gürpınar. The Unionists tried to solve the Armenian issue, which had been a thorn in the Ottoman side ever since the days of Sultan Abdülhamid II (1876-1908) and the Treaty of Berlin (13 July 1878), and particularly the latter’s Article 61, which made the “Armenian Problem . . . an international problem.” The political scientist and historian Dr Fuat Dündar matter-of-factly posits that the Unionists “implemented population policies according to the [principle] of Islamization . . . All non-Muslims, especially the Armenians along with Rums (Ottoman Greeks) and Eastern Christians . . . were subjected to expulsion and resettlement in order to create a new Anatolia with more homogenous and loyal communities.” The aim was the creation of a Muslim homeland in the Ottoman heartland, where Muslim Ottomans could live and thrive, united in their Ottoman citizenship and allegiance to the Sultan-Caliph residing in Istanbul. The Balkans War (1912-13) had earlier decisively proven that Christian Ottomans were not to be trusted, as they obviously preferred political independence over loyalty to the Ottoman state.

In this context, my usage of the noun Muslim does not necessarily denote personal piety or particular devotion (though on an individual level these traits should not be discounted), rather, I would suggest, the Unionist leadership wielded the religion of Islam as providing a common identity and goal, superseding ethnic and/or linguistic solidarity and togetherness. Though many historians and commentators regard the Unionist position as Turkist and hence nationalist avant-la-lettre, I would like to contend that the Committee for Union and Progress was primarily Ottomanist in its outlook, meaning that they strove to uphold Ottoman citizenship as defined in the first Ottoman Constitution (1876), and as a result, following the Balkan Wars, the Unionists attempted to forge a novel form of Ottomanism, a common citizenship beholden to Islam and the Sutlan-Caliph.

Returning to the Armenian issue, the Paris-based political scientist Prof. Dr. Hamit Bozarslan unequivocally states that, not quite 37 years after the Berlin Treaty, the “extermination of the Armenians started in the wake of the Deportation Act (Tehcir Kanunu) adopted on April 24, 1915, and was LARGELY finished before the end of the same year.” At the time, the New York Times carried numerous pieces dealing with the Armenian atrocities (according to the foreign correspondent John Kifner, ‘145 articles in 1915 alone’). On 7 October 1915, for instance, the paper reported that James Bryce (1838-1922), erstwhile Regius Professor of Civil Law (1870-93) and British Ambassador to the United States of America (1907-13), had testified before the House of Lords that “the figure of 800,000 Armenians destroyed was quite a possible number.” In the run up to the proclamation of the Republic in 1923, the Kemalist Ankara government pursued its own policy of ethnic cleansing with regard to the so-called Pontus Greeks living on the Black Sea littoral, a topic I have dealt with in 2008. These Unionist population policies created the breeding ground for the nation state Turkey, largely based on Anatolia with a small foothold on Europe’s eastern flank. Originally these territories functioned as a Muslim Ottoman homeland, which was subsequently re-defined as a Turkish homeland. The above-mentioned Kemalist authorities’ “policy of Turkification” effectively provided the various ethnic groups and sub-groups living within the nation state’s borders with a new identity, from being Ottoman Muslims beholden to the Sultan-Caliph residing in İstanbul, they became Turks (or Turkish citizens, as stipulated in the 88th article of the Republic’s Consitution, accepted on 20 April 1340/1924) tied to the figure of Mustafa Kemal (to be surnamed Atatürk in 1934, 1881-1938), the first and ‘eternal’ President of the Republic of Turkey and to the nation state he founded (Following his untimely death, Atatürk was proclaimed the nation’s ‘Eternal Chief’ or Ebedi Şef on 26 December 1938).

Back to the Future: The Past is in the Present

Turkey’s President Tayyip Erdoğan.

As an homegrown Turkish Islamist political movement, the AKP originally took part in pious Turkish Muslims’ hatred and dislike of the figure of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. But in time, the Prez and his henchmen have co-opted this figure, as a foil for their personal goals and ambitions. Such a development has led towards to the figure of Recep Tayyip replacing that of Mustafa Kemal: “Erdoğan [has now] become another Atatürk for the Turkish nation. Whereas the first President (1923-38) ushered his fellow-Turks into the modern world, arguably shedding any excessive traits of their Islamic persuasion in the process . . . starting [in] 2014 [, Erdoğan has by now largely] complete[d] this task [of creating a new homeland] by means of reviving the Turks’ ties to their Muslim creed and uniting all the ethnic groups and sub-groups living on Anatolian soil under the banner of Islam,” as I have argued in the summer of 2014. And in that context, the issue of Armenian massacres perpetrated in the course of the Great War (1914-18), that have become known as the Armenian Genocide in the aftermath of World War II, originally fulfilled an important role in Tayyip Erdoğan’s plan to connect the New Turkey with the “first assembly of what was to become Turkey’s parliament on 23 April, 1920.” This pre-republican Grand National Assembly (Büyük Millet Meclisi or BMM), which effectively constituted the Ankara government that led the War-of-Independence (1919-22), “consisted [solely] of representatives of Anatolia’s Muslim population.”

In 2014, then still-PM Tayyip Erdoğan took the unprecedented step of offering his condolences to the Armenian people in nine different languages, including Armenian, on the prime-ministerial website: “Millions of people of all religions and ethnicities lost their lives in the first world war . . . Having experienced events which had inhumane consequences – such as relocation – during the first world war should not prevent Turks and Armenians from establishing compassion and mutually humane attitudes towards one another. It is our hope and belief that the peoples of an ancient and unique geography, who share similar customs and manners, will be able to talk to each other about the past with maturity and to remember together their losses in a decent manner. And it is with this hope and belief that we wish that the Armenians who lost their lives in the context of the early 20th century rest in peace, and we convey our condolences to their grandchildren,” as can now be read the Guardian website as the original prime-ministerial webpage no longer seems to exist. At the time, I conjectured that this gesture on the 99th anniversary of the 1915 events could usher in an AKP-led drive to downplay the ideological glue that is nationalism and instead stress a common spiritual heritage of the Muslim and non-Muslim inhabitants of Anatolia (“an ancient and unique geography”) – a common spiritual heritage expressed in either Islam or Christianity.

The 2014 prime-ministerial message fell short of acknowledging the Armenian Genocide, but could be seen as a first move towards a more realistic form of coming to terms with the past or Vergangenheitsbewältigung, to use the arguably somewhat unwieldy German term. Alas, this proved but a futile hope, as the following year (2015), the Turkish government once again pushed its denialist narrative in response to global centenary commemorations of the implementation of the Deportation Act (Tehcir Kanunu), leading to wholesale genocidal consequences in weeks and months to come. In fact, as the issue of symbolic dates and their meaning is a hot topic in Turkey, that year, Ankara moved the culmination of the Gallipoli commemorations to the 24th instead of the 25th of April (known as Anzac Day by Australians and New Zealanders). Ohannes Kılıçdağı, a writer for Agos, an Armenian weekly published in Turkey, at the time declared that “[e]verybody knows that the two memorials around Gallipoli have been held on 18 March and 25 April every year.” Traditionally, the 1915 Ottoman victory at Gallipoli was celebrated as a major milestone in Mustafa Kemal’s career path which was to reach its climax in the 1923 foundation of the Republic. But today, in AKP-led post-Kemalist Turkey, the military success at Gallipoli is taken as proving that Ottoman Muslim conscripts saved the day by defeating Christian invaders intent on partitioning the Ottoman lands. In fact, both commemorations seem to stress the primacy of Islam in Anatolia: the military victory momentarily saved the Muslim Ottoman state which was to become the Turkish nation state, and the Deportation Act (Tehcir Kanunu) initiated the final expulsion of non-Muslims from the Anatolian mainland by means of a ruthless and effective form of ethnic cleansing.

The Turkish Republic’s Raison d’être: The invented tradition of Turkish denialism

In time, the AKP adoption of the traditional Turkish denialist discourse has gotten stronger and more determined, particularly in the aftermath of the 2016 Coup-that-was-no-Coup, which ultimately led to an informal alliance between the Islamist AKP and the Islamo-fascistoid MHP (or Party of the Nationalist Movement). Since February 2018, this informal pact became an electoral alliance carrying the name ‘People’s Alliance’ or Cumhur İttifakı, in Turkish. But five years ago, Tayyip Erdoğan was all but on the verge of reconciling with the infamous G-word, yet now he has performed a total U-turn allowing him to seek a connection with the infamous ‘invented tradition’ of Turkish denialism (to use the 1983 Hobsbawmian coinage). For, as Dr Doğan Gürpınar reminds us, in Turkey “the year 1915 was a non-issue before the assassinations of Turkish diplomats as revenge by the ‘Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia’ (ASALA) in the 1970s.” Gürpınar explains that “institutionalized Turkish denialist discourse was formulated and developed only in the 1970s and even the 1980s as a response to the rise of the Armenian genocide agenda as an organized cause by the late 1960s and became an issue of public attention in Turkey after decades of oblivion.” After all, in 1919, the British Empire pressurised the defeated Ottoman government of Istanbul to set up a Courts-Martial to try individual Unionists, government officials, and military leaders, as well as other functionaries, with charges of committing crimes against the Armenians and subverting the Ottoman constitution (1876/1908) by leading the Empire into the Great War (1919-22). This was done in response to a joint declaration by Britain, France and Russia issued on 24 May 1915 to “hold personally responsible . . . all members of the Ottoman government and those of their agents who are implicated in such massacres.” In 1922, the “Court Martial pronounced, in accordance with said stipulations of the Law the death penalty against Talaat, Enver, Cemal [Pashas], and Dr. Nazim,” having found them guilty of “massacre, plunder of goods, appropriation and hoarding of riches.” Two of the three guilty Pashas had fled the Ottoman lands and were later assassinated by Armenian terrorists in the course of the so-called Operation Nemesis. In this way, the Armenian massacres which were to be named erroneously the ‘First Genocide of 20th Century,’ received their legal and judicial resolution right before the Kemalist victory and the subsequent foundation of the Republic of Turkey. As I explained in 2014, “many commentators and even historians refer to the Armenian issue as the 20th century’s first genocide, [though] in reality the German Empire under Kaiser Wilhelm II (1888-1918) had already constituted a precedent previously.” As expressed by the Dutch Professor of African History “Jan-Bart Gewald ‘[b]etween 1904 and 1908 Imperial German troops committed genocide in German South West Africa (GSWA), present-day Namibia.’ Germany’s late and short (‘about thirty-five years,’ as expressed by the sociologist Gurminder K. Bhambra) entry into Europe’s colonial game overseas led to extreme measures. In South West Africa, German settlers employed the Herero-German war to ‘rightfully’ occupy territory belonging to the Herero tribes. This land-grab was preceded by ‘the planned and officially sanctioned attempted extermination of the Herero people.’ As the Ottomans had enjoyed good relations with the German Empire ever since the early years of Sultan Abdülhamid II (1876-1909), it would stand to reason to assume that the Unionists were eager to apply the German experiences in South West Africa to their own territorial designs for Anatolia.” In this way, the Unionist government implemented a strict policy of ethnic cleansing to clear occupied territories in order to populate them with new arrivals – Muslim refugees fleeing war and persecution in the Balkans and the Russian Empire. These population policies created the ground for the territorial expression of Turkish nationalism as understood by the Kemalist leadership, first developed in 1922 (as I have conclusively illustrated in 2008). And today, the post-Kemalist New Turkey as the temporal successor of the nation state founded by Atatürk and self-proclaimed heir to to the Ottoman Empire finds itself forced to continue the habits and rituals of the infamous ‘invented tradition’ of Turkish denialism

Turkish Denialism and Alternative Facts

At the White House (13 November 2019), the New Turkey’s Prez reaffirmed his commitment to the tenets of denialism: “Historians not politicians should make a decision concerning an issue that was experienced 104 years ago during [the prosecution of] a war. Turkey is on the side of dialogue and free discussion. Our proposal to the Armenian side of setting up a joint historical commission is still valid. In the archives of our armed forces more than one million documents are available.” In the same breath, he went on to suggest that H. Res. 296 was introduced by U.S. lawmakers sympathetic to the PKK/YPG/PYD (the latter being the Democratic Union Party) nexus, an entity more commonly known as the “Kurds,” and, in response, the U.S. President actually came out with the statement that Tayyip Erdoğan has “a great relationship with the Kurds. Many Kurds are living currently in Turkey and they’re happy, and taken care of, including healthcare and education,” and adding “[t]his has been thousands of years in the process between borders, between these countries and other countries that we’re involved with 7,000 miles away.” This statement is a prime example that really shows that Donald Trump has no idea what he is talking about most of the time. In fact, the Democratic Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi’s remark that the President is “an imposter . . . [that] knows full well that he’s in that office way over his head,” does spring to mind. Admittedly, Pelosi’s words were spoken in the context of the ongoing impeachment hearings, but appear strangely apposite here.

The situation of the Kurds in the Middle East is a complex matter that cannot be contained in soundbites and catchy phrases. As I wrote last January, “Turkish and Kurdish populations have been sharing space in the same locality for centuries – for ‘four hundred years of more,’ as verbalised by Dr Christopher Houston.” Dr. Janet Klein, an expert in late-Ottoman Kurdistan, for her part, simply said that “[t]he idea that Turks and Kurds have been engaged in conflict for centuries is very ahistorical.”

Still, in the West, the perception is that Turks and Kurds are continuously at each others’ throats. In reality though, the current enmity between the Turkish state and the Kurds, or rather the PKK (Kurdish Workers’ Party or Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê), goes back to the 1980’s: “The PKK has been waging a bloody war against the Turkish state for more than 30 years now. At first, this struggle aimed at the creation of an independent Kurdistan in the south-eastern Anatolia, but in time, these separatist demands have become calls for local autonomy and cultural recognition. The AKP was the first political organization in Turkey to officially acknowledge the existence of a Kurdish issue, and the first one to attempt to tackle the deadlock by means of a negotiation process, known as the ‘Kurdish overture’ launched in 2009. But following the inconclusive June 2015 elections and Turkey’s subsequent November Surprise [as I have termed the surprisingly unsurprising AKP electoral victory on 1 November 2015] that saw the AKP receive a veritable mandate for the construction of a post-Kemalist century, Ankara has once again started beating the war drums,” as I have written in 2016. And these war drums have now led the Turkish Army and its Jihadi FSA allies into northwestern Syria. The Prez announced his designs on 24 September at the United Nations General Assembly in New York: “Our intention is to establish the possibility for 2 million Syrians to settle down in a safe zone we plan to set up.”

Good Ottoman Precedent: Turkey as an Islamic State

The Canadian journalist and writer Nick Ashdown recently put it like this: “Erdogan has long seemed comfortable using demographic engineering as a political tool. Indeed, he has threatened to use Middle Eastern refugees as a weapon against Europe, repeatedly warning he could ‘open the gates’ and flood Europe with the Syrians currently living in Turkey. He also seems quite comfortable opining on which groups belong where in Syria. ‘Arabs are most suitable for this area,’ he told journalists during an interview on Oct. 24.” The Prez namely spelled out his intentions there and then: “Those areas aren’t appropriate for Kurds’ lifestyles, because they’re desert.” For, as should be quite common knowledge by now, the Kurds have ‘no friends but the mountains.’ Ashdown rightly points out the “worrisome historical resonances of Erdogan’s proposed policy” namely “[s]tate-facilitated or state-enforced population transfers have a long history in the former Ottoman Empire and have left an indelible imprint on northern Syria in particular. Known as sürgün (‘deportation’ or ‘exile’) during Ottoman times, they were often used as a form of politically motivated demographic engineering.” After all, the Prez and his AKP henchmen just love to operate in accordance with good Otttoman precedent. The notorious 1915 Tehcir Kanunu, for instance, aimed at deporting Ottoman Armenians to Deir Ezzor in the Syrian desert: “Armenians were killed, the majority of them through death marches periodically interrupted by mass killings. Concentration camps in Syria’s Deir Ezzor were some of the final destinations for those who survived the marches,” as explained by Ashdown.

Though the Prez is keen on good Ottoman precedents, his view of historical reality does not necessarily square with the facts on the ground. Following his White House visit, he went to the Washington Diyanet Center, a purpose-built architectural propaganda vehicle for the AKP-led New Turkey in the new world, where he said the following absurdity, which is really beyond any need to receive a form of correction: “They [Armenians] used to travel in different places as nomads. The forced deportation took place while they were living the same way as nomads in Turkey.” It seems that over the past years, Tayyip Erdoğan has made a most amazing intellectual journey, a journey which has taken him from a point of near-reconciliation – to his current location where he seems to follow his U.S. counterpart’s example closely and does not shy away from making-up alternative facts to suit his agenda. And this means that the issue of the Armenian Genocide will continue to fester and simultaneously, the invented tradition of Turkish denialism will, in turn, continue to thrive in the post-Kemalist and pseudo-Ottoman era ushered in by the Islamist political movement set up none other than Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Whether nationalist or Islamist, the invented tradition of Turkish denialism seems set to persist, and persist for as long as there is a Turkish Republic.

***

21WIRE special contributor Dr. Can Erimtan is an independent historian and geo-political analyst who used to live in Istanbul. At present, he is in self-imposed exile from Turkey. He has a wide interest in the politics, history and culture of the Balkans. the greater Middle East, and the world beyond.. He attended the VUB in Brussels and did his graduate work at the universities of Essex and Oxford. In Oxford, Erimtan was a member of Lady Margaret Hall and he obtained his doctorate in Modern History in 2002. His publications include the revisionist monograph “Ottomans Looking West?” as well as numerous scholarly articles. In Istanbul, Erimtan started publishing in the English language Turkish press, culminating in him becoming the Turkey Editor of the İstanbul Gazette. Subsequently, he commenced writing for RT Op-Edge, NEO, and finally, the 21st Century Wire. You can find him on Twitter at @TheErimtanAngle. Read Can’s archive here.

READ MORE TURKEY NEWS AT: 21st Century Wire Turkey Files

SUPPORT OUR MEDIA PLATFORM – BECOME A MEMBER @21WIRE.TV